Why do so many French women – and not just powerful women in politics and the media – see DSK as the victim?

Listening to the French equivalent of BBC Radio 4 this morning (France Inter) brought it home to me: France is one of the last great patriarchies. I could hardly believe my ears. There, in the recording studio, a female journalist called Pascale Clark sat tittering at male comedian, Sami Ameziane, who was impersonating DSK in his hotel room in New York trying to talk some sense into his penis: “Listen I don’t like the look of this chick, she’s going to get you into trouble, put away the merguez, buddy…” But it’s the other voice that wins: “Come on Dom. Have you forgotten who you are, Dominique-nique-nique-nique*. Whip out the tools, mate…” The three minute sketch was a festival of macho inanity the subtext of which was, either the maid was asking for it and changed her mind half way through, or it was a set-up. In both scenarios DSK is the ‘vigorous’ male (as Christine Boutin described him), a Samson figure, being brought low by a woman.

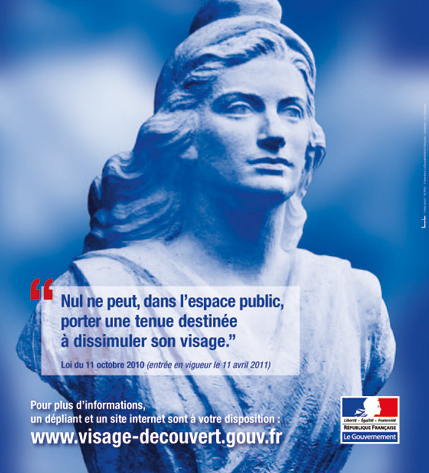

When Segolene Royal ran for the presidency, I was stunned by the misogynistic comments, from both men and women, that polluted her campaign. When she failed to get elected I wondered if it was what the French call a strategie d’echec, her own unconscious urge to fail, because she was not ready to question her own conditioning. Today, the widespread view of DSK as a victim confirms my misgivings. Willfully unreconstructed, France is a society in which women collude in a continued phallocracy.

If Brits and Americans want to understand this mindset all they have to do is watch Joan Holloway, the curvacious redhead in Madmen, a TV series set in an advertising agency in 1960s America. Joanie is clever, sexy, witty and submissive. She’s admired, valued, often worshipped and always dominated. This is the unspoken pact most French women are still willing to accept.

*nique : screw