This month, a bill making the wearing of the burqa* illegal in public will become law in France. Predictably, as an Englishwoman I have mixed feelings about this law. On the one hand I agree with Sarkozy’s former minister, Fadela Amara, who like the majority of her fellow French Muslims, objects to the burqa as a symbol of religious extremism and patriarchal oppression. On the other, I believe that laws targeting religious practices ought only to be considered if they represent a threat to individual or public safety. My first instinct in moments such as these is to ask my French-born children what they think. My 23 year-old daughter sees me coming. “My opinion,” she begins. “Is quite radical. And quite French. When I see a woman walking down the street in a full veil I immediately picture the husband who is making her wear it.” My daughter approves of the ban because behind the burqa she sees a life of ostracism and male domination. My son is also for the ban and his argument runs like this: the form of Islam that suggests that a woman’s face must be covered in order to preserve her decency is inferring that women are intrinsically indecent, an idea that is not only appalling but contrary to the values of French society. I can understand both these positions. The trouble is, I’m deeply suspicious of the motives behind this law and this colours my view, not only of its justice but of its efficacy.

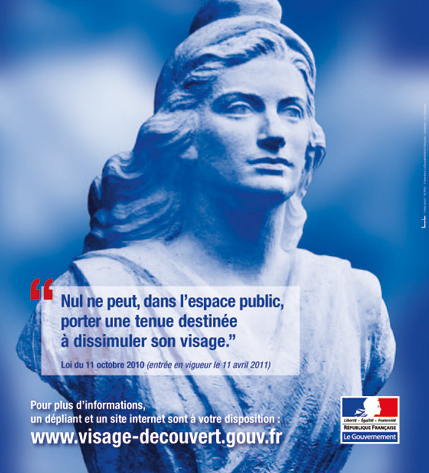

Unlike the law of 2004, which banned the Islamic headscarf (hijab) in French state schools, the wording of this new law against the burqa is deceptively simple. “No one may, in a public place, wear a garment designed to conceal the face.” No mention this time of religion, or values, or of that sacred cow, la laicite. The government campaign surrounding the ban is purposefully ambiguous and designed to suggest that this is not so much about Islam or French identity as it is about some undefined form of practicality. The campaign slogan, “La République se vit à visage découvert” can only be loosely translated into English as, “We live the Republic with our faces uncovered/without a mask.” It is not surprising in this context that a list of exemptions to the law are being drawn up and will include motorcycle couriers, carnival revellers and people with bird flu. (One cannot help wondering about cases like Lady Gaga.)

Unfortunately, however, recent events suggest that this is a law about Islam and a further example of the rather ugly finger pointing that has been going on since the beginning of Sarkozy’s presidency. In the months since the President first announced, during his somewhat overblown performance at Versailles in June 2009, that “the burqa is not welcome in France”, he and his party have adopted a discernible strategy of political harassment of the Muslim community, all of it designed to win votes from the extreme right. After launching, in November last year, a public debate on the rather nebulous question of French national identity, Sarkozy cut to the chase in February this year and announced a new, even meatier debate on the place of Islam in France. Strong in the knowledge that 42% of French people now believe Islam to represent a threat to the nation and knowing that the burqa is worn by only a tiny fraction of France’s Muslims (about 2000 women), Sarkozy clearly believed he could use this law to whip up yet another wave of anti-Muslim sentiment without getting burned. It now appears he was wrong. In seeking to occupy and thereby legitimising the ideological ground of the extreme right he now finds himself neck and neck with Marine Le Pen in voting predictions for the next Presidential elections. Alarmingly, a recent poll foresees the head of the National Front knocking him out in the first round. Sarkozy’s strategy, then, to gather a consensus around the febrile issue of French identity, has worked but in the process he has shot himself in the foot.

The place of Islam in France will doubtless lie at the heart of the next elections but fermenting mistrust towards her Muslims is unlikely to result in their jubilant desire to throw off the veil and live the republic to the full.

*understood in France as the full veil (niqāb) covering the face.

NB A version of this post appears in this month’s Prospect Magazine (Online)